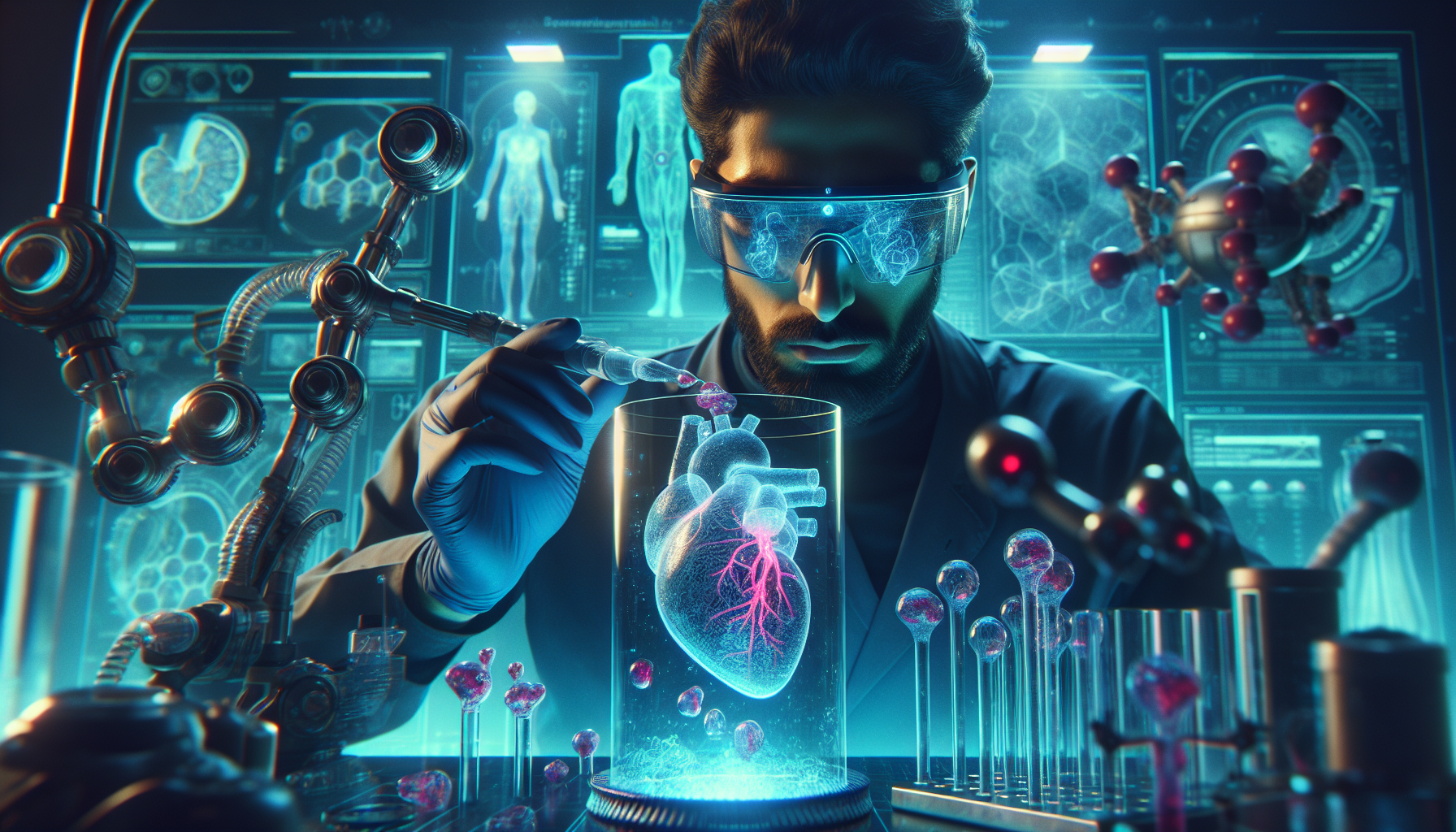

3D printing started as a neat party trick for hobbyists. Now it’s pumping out jet engine parts, prosthetic limbs, and entire houses. Medicine, never one to sit out a revolution, saw an opportunity: why stop at plastic when you can print living tissue?

The catch? Biology is messy. Cells don’t behave like molten plastic, and human tissue doesn’t appreciate being forcibly extruded into shape. Blood vessels, in particular, are a nightmare—tiny, branching, and prone to collapsing into a gooey disaster.

Enter gallium. A metal that melts at room temperature but won’t poison the host. The U.S. National Science Foundation funded a team at Boston University and Harvard’s Wyss Institute to put it to work. Their process, ominously dubbed ESCAPE (Engineered Sacrificial Capillary Pumps for Evacuation), uses gallium to create temporary molds for 3D-printed tissues. When the structure sets, the gallium is removed, leaving behind a vascular network so intricate it could pass for the real thing.

Christopher Chen, director of BU’s Biological Design Center, spearheaded the project with one goal: to print functional blood vessels. “Blood vessel networks feature many different length scales,” he said, as if that were a simple challenge. His team succeeded—veins, capillaries, and even diseased tissues, all built to spec. Because why stop at printing healthy tissue when you can simulate illness, too?

The implications are wild. If ESCAPE scales up, donor organ shortages could become obsolete. Need a new liver? Print one. In a slightly more cyberpunk twist, wealthy buyers could commission custom-built biological enhancements. Medicine and bioengineering are fusing into something entirely new, and the ethical guardrails are looking flimsy.

For now, the method remains experimental. But with AI refining biological blueprints and researchers pushing the limits of biofabrication, full-scale organ printing isn’t a matter of “if”—it’s “when.” Somewhere, in a dimly lit lab, someone is already whispering, “It’s alive.”

Five Fast Facts

- Gallium melts in your hand—but won’t poison you like mercury would.

- Boston University’s Biological Design Center also works on growing synthetic muscle tissue.

- The Wyss Institute is named after Hansjörg Wyss, a billionaire who made his fortune in medical devices.

- 3D bioprinting was first demonstrated in 2003 using modified inkjet printers.

- Scientists have already 3D-printed functional human ears and corneas.