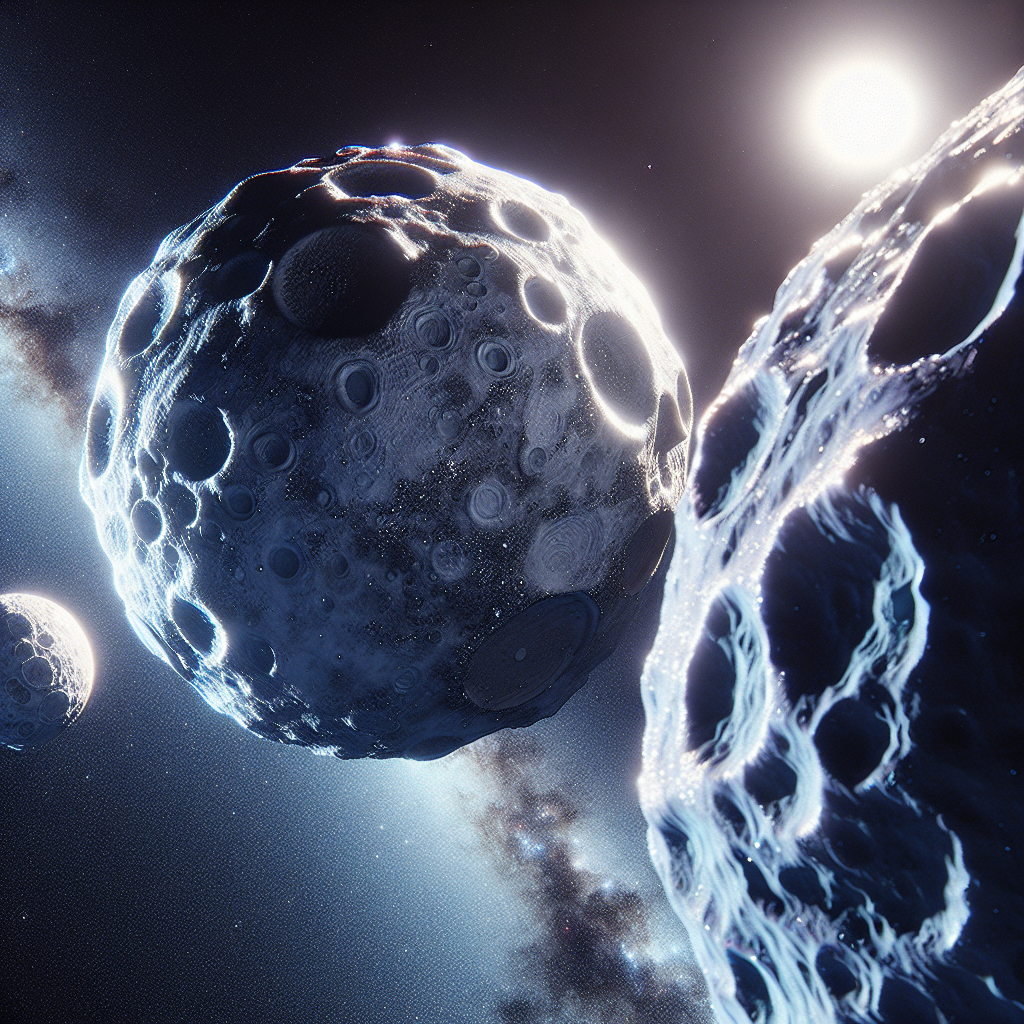

The three-body problem has haunted mathematicians for centuries. Predicting how three gravitationally entangled objects move is a nightmare of chaotic physics, famously explored in the novel-turned-Netflix-show *The Three-Body Problem.* But out in the icy void of the Kuiper Belt, a trio of space rocks seems to have cracked the code.

Meet 148780 Altjira—a frigid, ancient system that might be the second stable trinary object ever found in the Kuiper Belt. If this holds up, it means our solar system might be hoarding secret triples, waiting to be exposed. And that could rewrite theories on how these distant objects formed in the first place.

“The universe is packed with three-body systems,” says Maia Nelsen, lead author of the study and recent Brigham Young University physics and astronomy graduate. “Alpha Centauri, the closest star system to Earth, has three stars. Now, it looks like the Kuiper Belt is following the trend.”

KBOs—Kuiper Belt Objects, if you’re not on speaking terms—are the icy fossils of our solar system’s unruly youth. Over 3,000 have been cataloged since the first one was found in 1992, but that’s barely the tip of the interstellar iceberg. The biggest KBO? Pluto. And if Pluto is involved, you know things get weird.

Here’s where it gets even more interesting. This discovery supports an idea that KBOs didn’t just smash into existence like cosmic fender benders. Instead, some might have formed as trios from the gravitational collapse of primordial material around our newborn Sun. Stars do this all the time—why not chunks of frozen rock?

Altjira sits a comfy 3.7 billion miles from the Sun, a leisurely 44 times the distance from Earth. Hubble images show two tightly bound KBOs with a third one orbiting farther out. But here’s the kicker: That inner object isn’t one body. It’s actually two—so close together that even Hubble’s cameras can’t tell them apart.

“With objects this tiny and this far away, their separation is a fraction of a pixel on Hubble’s camera,” Nelsen explains. “You have to use non-imaging methods to figure it out.” Translation: It takes an absurd amount of patience and cold, hard data crunching.

Seventeen years’ worth of observations from Hubble and the Keck Observatory reveal the outer rock wobbling just enough to hint that the inner mass isn’t singular. A clever bit of orbital detective work later, and boom—it’s a triple.

“Over time, we saw the orientation of the outer object’s orbit shift,” says Darin Ragozzine, another Brigham Young scientist. “That told us the inner mass was either an insanely elongated object or two separate bodies.” Spoiler: It was two.

If more of these trinary systems lurk in the Kuiper Belt, they could provide a key to unlocking our solar system’s messy, primordial past. For now, Altjira and its icy throuple hold their secrets tight, 3.7 billion miles away.

Five Fast Facts

- The Kuiper Belt is named after Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper, who ironically predicted that it wouldn’t actually exist.

- Altjira is named after an Aboriginal deity from Australian mythology, known as the creator of the sky world.

- The three-body problem is so complex that no general solution exists—even supercomputers struggle with it.

- Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet in 2006, but some astronomers are still fighting for its planetary rights.

- The Alpha Centauri system, another three-body system, is the closest star system to Earth at just 4.37 light-years away.