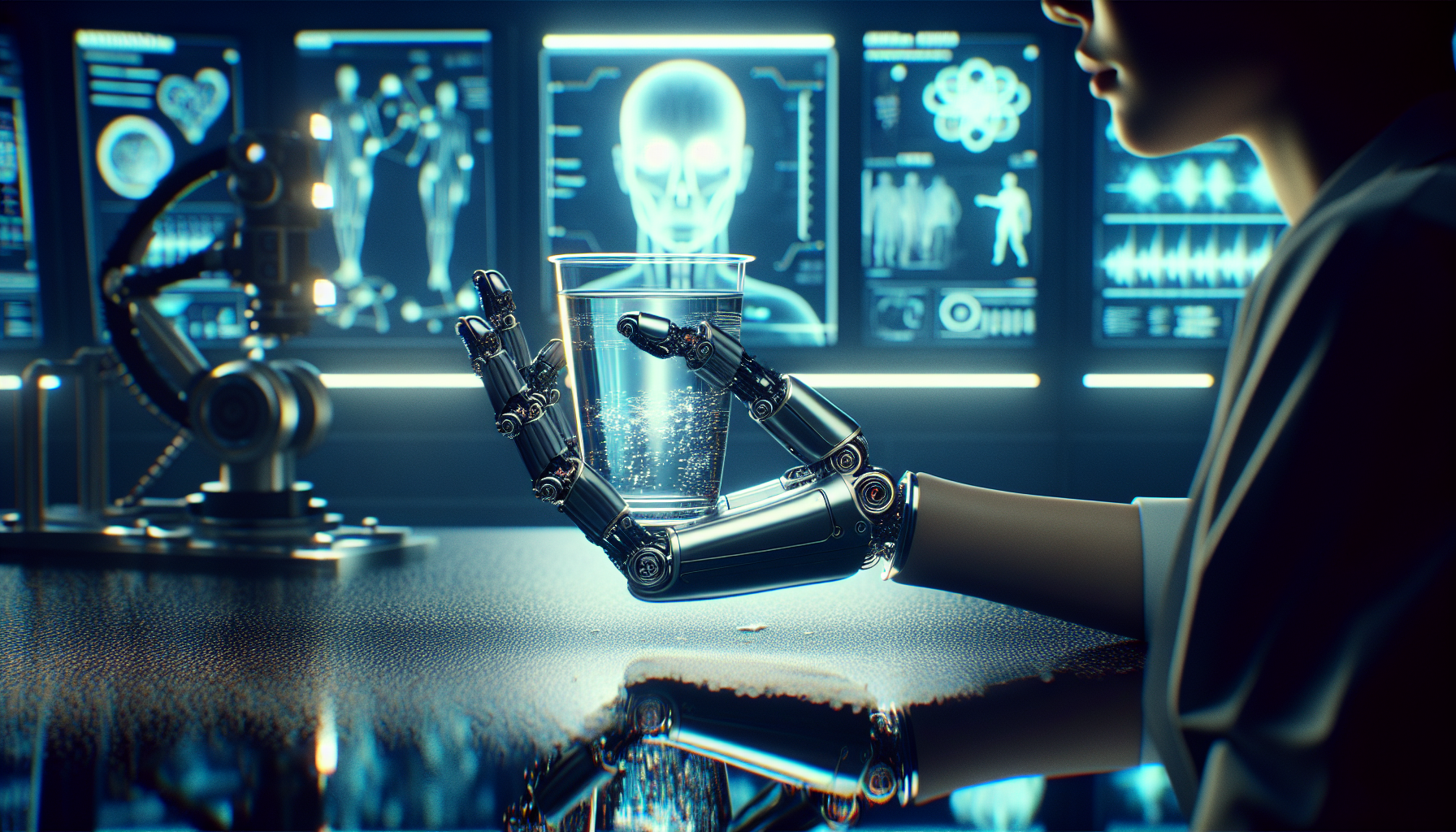

Johns Hopkins engineers have finally built a robotic hand that doesn’t grip like a vice or flop like a dead fish. This one actually knows what it’s holding—plush toys, water bottles, sponges—and adjusts its grip accordingly. It’s the closest thing yet to a cybernetic hand that thinks before it squeezes.

Most robotic hands are either too stiff or too soft, making them unpredictable at best and destructive at worst. But this one? It blends rigid structure with soft, air-filled joints—much like an actual human hand. The result is a prosthetic that won’t crush a Styrofoam cup or drop your keys down a storm drain.

The research, published in *Science Advances*, details how this hybrid system mimics the mechanics and sensory abilities of flesh-and-bone hands. The three-layered tactile sensors, inspired by human skin, do more than just detect touch—they recognize shape, texture, and pressure. That means no more robotic death grips on fragile objects.

“The goal has always been to create a prosthetic that feels and functions like a real hand,” said Sriramana Sankar, the biomedical engineer leading the project. “People with upper-limb loss should be able to pick things up, hold their loved ones, and interact with the world without hesitation or fear.” In other words, no accidental bone-crushing hugs.

This isn’t the lab’s first dive into bionic sensation. Back in 2018, they pioneered an electronic “skin” that could actually feel pain—because why stop at touch when you can replicate suffering? This new hand takes that concept further, feeding sensory data to the user’s nerves via electrical stimulation. In theory, this means a person using it could feel the difference between, say, a sponge and a metal pipe without looking.

During lab tests, the bionic hand tackled 15 everyday objects ranging from soft plush toys to rigid metal bottles. It nailed a 99.69% success rate, adapting its grip in real time to avoid crushing, slipping, or turning delicate items into debris. The highlight? Gracefully picking up a flimsy plastic cup filled with water—one-handed, three fingers, no dents, no spills.

“We’re merging soft and rigid robotics to mirror the human hand,” Sankar explained. “A real hand isn’t just stiff or floppy—it’s a hybrid system.” The result is a prosthetic that doesn’t just work; it works like an actual, living hand.

This isn’t just good news for people with limb loss. Advances like this reshape how robots interact with the world, opening doors for everything from AI-assisted surgery to humanoid androids that don’t fumble every object they touch. The future of robotics isn’t just about movement—it’s about understanding, adapting, and maybe, just maybe, feeling.

Five Fast Facts

- Johns Hopkins researchers also developed the world’s first electronic skin that could feel pain—because robots deserve suffering too.

- The human hand has 27 bones, but this prosthetic achieves similar dexterity with far fewer moving parts.

- Early robotic hands were so rigid they could crush objects unintentionally—great for Terminators, not so much for human users.

- Soft robotics, like the air-filled fingers in this hand, were inspired by how octopuses manipulate objects.

- Despite advances, neural interfaces still struggle to replicate the full sensory complexity of a real human hand—but this one comes eerily close.